Last April my husband and I visited the Santa Fe area during Easter week and ended up looking for and finding New Mexican hand weavers.

On our way from the Albequerque airport we were surprised to see foot traffic on the interstate highway. These were people making a pilgrimage to the Santuario de Chimayo, the site where a crucifix of Our Lord of Esquipulas was found and a place known for its’ healing earth’. Some pilgrims were dragging a cross.

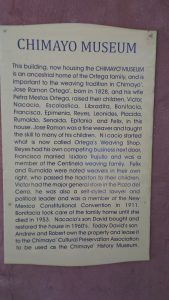

As we followed the pilgrims to Chimayo, we also found many weavers. It turned out that the village has been a center of weaving since settlers arriving from Old Mexico reached northern New Mexico in the 1700’s.

The immigrants came as settlers first and later identified themselves as farmers and ranchers. Weaving was a necessity to clothes themselves, furnish their homes and to use as trade goods.

It is important to point out here that the New Mexican rug weavers are not the same as the Navajo rug weavers. They come from a different background and use a different type of loom. Occasionally they may borrow each others’ patterns but they are still different. The Churro sheep were brought into the New World and New Mexico by the Hispanic settlers and they turned out to be the the perfect sheep for the southwest. Both the Indians and the Mexican Americans used their wool and the rest of the animal.

I noticed that every store and shop that I visited in Santa Fe, Taos, Chimayo and nearby areas that featured textiles/ Southwestern art/ curios,etc. had a loom set up somewhere on the premises and all had textiles in progress on them. Most of them were making rugs or similar material to be used for vests and jackets. On close inspection, all these textiles seemed to be well done. However, the village of Chimayo seemed the center of weaving. There were several shops that sold local arts and rugs but two stood out. They were both families that had been weaving for several generations.

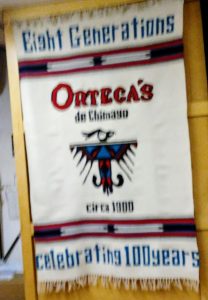

The Ortegas

According to local history, the first Ortega weaver was Nicolas Gabriel Ortega. A descendant, Nicasio Ortega, opened the first weaving shop in Chimayo in 1918.

Before that, pieces were being sold by weavers in the area from their houses or through jobbers who contracted weavers for their work and resold them to shops catering to tourists.

The Ortega family advertises that they have been weaving and selling their output for 9 generations. I met the current owner , Robert Ortega,when I visited his store and workshop which are both open to the public.

plaque |

Robert Ortega |

It is near the original 1918 store but completely updated. Except for the looms. Some of them dated to the turn of the last century.They all are heavy duty two harness looms and the weaver stands on the treadles when weaving.

vests and small pieces for sale |

small loom |

The weaving shop and the adjacent Galeria Ortega were bright, welcoming and interesting. The studio had several looms set up and some weavers were at work making rugs, blankets, and the material for vests, coats and other unique items. Obviously the Ortega family has found a way to build on their background and history to market these iconic pieces.

The Trujillo Family

Around the same time that the Ortega antecedents arrived, the Trujillos came, too. They came as settlers from old Mexico to New Mexico and brought with them horses, sheep, missionary priests and soldiers and, as much as they could, the things they would need to open up and settle in a new land.

They settled in what is now Chimayo, in the shadow of the Sangri de Cristo Mountains and began the work of survival. The built homes and fortifications, shepherded their flocks, plowed and planted their fields and continued with their lives.

Weaving was a necessity to replace clothing and to soften their hard life with blankets and rugs. The wool came from their flock and – although white, black and grey wool was at their finger tips- vegetable dyes using local plants soon brightened the weavings.

Woven goods were used to barter, for it was a bartering economy, and apparently stayed that way until at least the mid 1800’s when tourists brought by the railroads began coming through.

Early tourism brought cash to the people for the weavings but it was haphazard and soon middlemen appeared to help with the exchange of money for goods. Soon jobbers were buying the weavings, placing orders for more, dictating the design, the colors, supplying the warp and keeping records of what they did.

In some ways the weavers lost control of their product. In other ways they learned what was necessary to set up a business.

Interestingly, in spite of the facts and figures, many of the dealers are remembered by Chimayosos today with great respect and fondness as they perceive these early dealers as helping the community through the Great Depression. They also are seen as having shepherded the community at large through the complex transition from barter system to market economy.

Fast forward to the 1st half of the 20th century. Here we meet Jacobo Trujillo, a young man who loved his home and his family. He began weaving when he was 14 years old using hand spun and hand dyed yarns. At age 16 he decided he needed a bigger loom and built one. He segued from his 20” loom to a 54” replica of one his brother-in-law owned- a 2 harness 4 treadle standing loom- and acquired his first experience of weaving large.

Jacobo began teaching weaving through a WPA sponsored program in 1932 -first at the University of New Mexico and following that at two high schools. It was during this time that he formulated his design theory and principals of weaving, as well as making notes on every aspect of weaving and yarn preparation.

By the end of the 30’s he was marketing his own weavings and taking special orders.

In 1935, Jacobo was now 24, he and his brother were offered a job of teaching Zunis how to weave outside of Gallup. They were thrilled! Their first task when arriving was to build two looms, which they did, and then they spent the next two month at their task. They each came home with money in their pockets.

Then came the 40’s. In 1942, Jacobo joined the U.S.Navy and was assigned to be a gunner on a merchant ship. However, in 1943 he was sent as instructor of arts and crafts in a rehabilitation program on Treasure Island (near San Francisco) where he taught leather tooling, tinwork, woodwork, spinning and weaving.

Here he became reacquainted with the woman who became his wife and he and Isabelle returned to the Chimayo area. He would hang on to his ranch land but Mr. and Mrs. Jacobo Trujillo both were employed at Los Alamos where they lived and raised their family for the next 30 years.

Jacobo, now called Jake, took up weaving again when his eldest child left home to go to school. Irvin was 10 years old when the loom was set up and he was curious and watched carefully.

Soon Irvin, too, was weaving. He mentions that his father was a good teacher and imbued in him traditional weaving techniques and traditions as well as encouraging innovation. Jake stressed that he should weave a different design on each piece.

Irvin loves weaving but made sure that he was qualified for positions that would support himself and his future family. He received a degree in civil engineering from UNM and then worked for the Corp of Engineers in Albuquerque. He moonlighted in a rock band—and that was how he met Lisa who was finishing her degree at UNM.

One of Lisa’s classes was in marketing and one of her assignments was to develop a business plan for a future business. She and Irvin discussed the assignment and she interviewed Jake about the subtleties of setting up a weaving business.

Fast forward a few years. Following their marriage and following her original class assignment business plan, they took the big step of becoming full time weavers and running their retail store, Centinela Traditional Arts.

Lisa Trujillo |

Irvin Trujillo |

They sell their own weavings, of course. and weavings by others. Some of the weavers are contracted, others are consignment artists. Lisa and Irvin support weavers as artists in their own right and encourage them to explore using their individual creativity.

The Store

Centinela Traditional Arts is eye candy! While most other establishments rely on commercially dyed commercial yarns, the Trujillos supplement their commercial yarn warps with vegetable dyed yarns and they even use handspun fibers in some of their weavings. They have also used the ikat technique which adds to the complexity and beauty of their work.

Irvin is in charge of the dyeing. His yarn room is a sight to behold with skeins of yarns in a multitude of beautiful naturally dyed colors glow from the racks on the wall. Hung in the Gallery are many of their works. You can see that they both follow Jake’s dictum of always making each piece different. Both Lisa and Irvin push the envelope and in their work one can see that they are always looking for ways of making their pieces stand out. Yes, they are faithful to the Chimayo tradition but, oh, lets try a few other techniques. Using handspun and hand dyed yarns is a step or several out of the ordinary. Why not try ikat? Irvin has done more than a few using that technique.

Chimayo |

Abstract |

Modern |

pictorial |

Chimay0 |

Modern |

Pictoral |

abstract |

|

Redwood Guild of Fiber Arts is excited to announce our May 2018 program featuring a lecture and workshop with

Lisa Trujillo, award winning weaver. Lisa and her husband Irvin are the owners of Centinela Traditional Arts in Chimayo, New Mexico. Their weaving has received recognition through articles, awards, museums, galleries and competitions. Their weaving is collected throughout the world, including the Smithsonian.

The lecture ” History of Chimayo Weaving” will be part of our guild meeting on Wednesday May 2. The workshop “Beginning Chimayo Weaving” is from Thursday Through Saturday May 3-5, 2018. Please check our guild website for more information about the lecture and workshop. athttp://redwoodgfa.org/