How wonderful would it be for an experienced California-based basket maker to be able to teach Mayan women in Guatemala a new skill–pine needle basketry—which would provide significant income to better their lives?

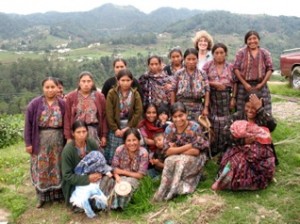

Michele Hament had the chance to find out when she spent 3 weeks in 2005, 2006, and 2009, in highland communities around Lake Atitlan. Michele was involved with Oxlajuj B’atz (“Thirteen Threads”), a non-profit indigenous women’s organization founded in 2004 through the collaboration of two Guatemalan-based Fair Trade groups, Maya Traditions and Mayan Hands. Oxlajuj B’atz’s mission has been to empower & educate Mayan women artisans so that they can improve their lives, and alleviate the adverse effects of poverty. The women Michele met with were members of village collectives organized by these organizations to provide some 300 Mayan women with knowledge and skills in healthcare, including medicinal plant use, business and leadership, craft techniques, & design & product development.

Michele notes that, “the irony of the situation was not lost on me: here I was, a gringa, going to teach basketry to people whose artistry and skill in backstrap weaving goes back many centuries.” But the tourist market for the weavings the Mayan women had been selling had been saturated, and didn’t provide sufficient income to enable the women to achieve financial independence.

Michele, a BABM member, has been a basket maker—and a basket teacher –since the early 1980’s, and works not only in pine needle baskets (many incorporating whimsy and unusual objects) but also willow and reed. She also makes eclectic and unique “small assemblages”.

She says that before traveling there, “I knew that Guatemala had these amazing pine needles” of superior length and weaving qualities. My hope was that we would work with them”. She planned to teach conventional pine needle stitching , and hoped that the Mayan women would adapt it to their own aesthetic.

Michele brought raffia with her, as well as books, patterns, and sample baskets, and then worked through Kaqchikel interpreters.

Only two of the communities she visited had traditions of basket weaving–both for local utilitarian purposes. In Santa Clara, the village men wove a variety of traditional baskets of native bamboo and cane for local sale, while in El Adelanto, women coiled simple baskets using pajon (similar to sweetgrass), and sometimes embroidery thread. Michele says, “these women took easily to working with pine needles and raffia, though some said they found them harder to work with than the pajon.”

Although she felt a commonality with the women through their shared language of art, she was at first concerned that they just wanted to copy what I was showing them. And while ultimately, women of two of original village co-ops without any basket-making tradition decided not to continue with basketry, the other four —including two with no history of basket-making – embraced the new craft.

El Adelanto group of Weavers |

Two groups of weavers from Panajachel |

On her second and third visits, Michele brought samples of new shapes and stitches, as well as instructions for dyeing the pine needles. “I was amazed at how quickly they were able to duplicate and pick up the new techniques”, and how they had adapted the designs. Eventually, the woman incorporated their own sense of aesthetics to create vibrantly colored designs, and, in El Adelanto, even integrated the pajon they had woven with previously.

Herlinda and her basket

These new baskets have found broader markets. With excellent on-line advertising through the Mayan Hands website (www. mayanhands.org) and a presence at fair trade venues in the U.S., demand has been exceeding supply, sending the now-expert women of Xeabaj into yet a new village to pass on their skills. And even the gift shop at the Smithsonian Museum now carries their artwork.

Dyed pine needle and bead basket by Eladelanto weaver |

Dyed pine needle and sweetgrass basket by El Adelanto weaver |

Impressively, Mayan Hand’s organizational goal of providing a steady income to women who previously survived on less than $1 a day has been reached, and workshops have now been offered not only in pine needle basketry, but also natural dyeing, needle felting and rug hooking. Significantly, the income that the women earn from their art today is determined both by the Mayan Hands program, and by the Mayan artists themselves.

Meanwhile, Michele has wonderful memories. When she last returned in 2009, the women covered the concrete floor of their co-operative building with fresh pine needles, and laughed with her at a video made the prior year of their first efforts. She was touched by a speech by a leader of the weaving group at Xeabaj, which thanked Michele for teaching a new skill for a better future. Translated first from Kaqchikel to Spanish, and then to English, it was a very moving experience.

For a gallery of Michele Hament’s basketry and other artwork, as well as information about her local workshops in the Bay Area, see: www.michelehamentartwork.com

For more information on Oxlajuj B’atz, see: www.weguatemala.org/en/ngo/oxlajuj-batz-thirteen-threadstrece-hilos

To see photos and prices of baskets currently for sale, see: www.mayanhands.org

Additionally, in the Fall 2013 issue of Surface Design Journal, Deborah Chandler has written an illustrated article, “Art and Opportunity in Guatemala,” which highlights this and other art programs offered to the Mayan highland communities.