Some of us saw the travelling exhibit “Gods in Color” at the Legion of Honor museum this autumn, and were enlightened, entertained or astounded by the recreations of the original coloring of some Classical sculptures and buildings. While it was fascinating to see previously pristine marble goddesses wearing colorful blouses, robes with embroidered flowers and blonde flowing locks, some of the more exotic garments certainly aroused our interest. What the heck were those diamond-patterned long sleeved blouses and leggings all about?

Good question, but not a fast answer. Our astonishment at these colorful statues is based on our misunderstanding, created by Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century art historians, of the appearance of “classical” Greek sculpture and architectural ornamentation. By the time it became fashionable in England and other European countries to collect ancient Greek and Roman statuary and remnants of buildings, such as the Elgin Marbles, they had endured almost two millennia of exposure to the elements. Standard museum treatment was to scrub a statue thoroughly with water to remove the dirt and grime of the ages, then put the glowing white object on display for the public. Naturally, those who visited museums or saw pictures of the statues assumed that this was the original condition of the artifact. This belief was reinforced by some art historians who cited them as evidence of a “higher aesthetic” in the Classical world.

Archaeologists and other scientists who had studied the statuary and building remains knew better. In sheltered locations, remnants of painted trim still existed and were documented in excavation reports; there were peculiar shadows and tints on excavated statuary, at least until it was cleaned. The experts talked to one another, and by the middle of the Twentieth Century, it was the common understanding among scholars that the ancients had been quite willing to paint details on their statues of gods and heroes as well as spice up the bas reliefs on their buildings with a bit, or even large quantities, of color.

I can still remember the shocked conversations in my freshman dorm dining hall one lunch in Fall 1961 when students returned from the mandatory Monday morning Western Civilization lecture. That day Hazel Hansen, Stanford’s leading art historian, lectured on her specialty, classical Greek sculpture. There were slides, most depicting clothed statuary, (since this was, after all, 1961 and 18 year olds were supposed to be relatively naïve) with brightly painted features, hair and garments. The general opinion was that this couldn’t be true, because “everyone knew” that the Greeks had such sophisticated tastes, and……….

Now we know that Professor Hansen was right. With the application of a variety of analytical techniques, scientists have not only figured out where paints were applied, but the colors and even the sources of the pigments. Once replicated, some of the decorative touches are downright garish. So yes, the Greek and Roman aesthetic was more Disney than dignified and the ancients have fallen from their pedestals to join the rest of us!

Now we’re back with the women in tights. Who are these people supposed to be, and why are they dressed that way? The Greeks told tales of people they called Amazons; their ceramics often have paintings of Amazons, some even captioned with non-Greek names. The Amazons are women, in the earliest ceramics painted wearing short Greek tunics while they fight with naked Greek warriors, but later dressed in what look like patterned tights and long-sleeved tops under long vests or shirts. They fought with spears, swords or bows and arrows. They might be the origin of the accusation that “You fight like a girl”, since the Greek warriors never wore pants, deeming them effeminate!

They were said to have cut off their right breasts so they could shoot their bows more accurately. A popular motif was the single combat between a Greek hero and an Amazon queen, where the hero only realized he was fighting a woman when he had dealt the fatal blow, her helmet flew off and he instantly fell in love with the beauty he had just killed. The “historians” of the time mainly derived their information from travellers and other tellers of tales, so we cannot trust their descriptions of a faraway Island of Women, Amazons killing all male babies (or giving them back to their fathers), waging war on Greek cities, roaming in war bands to seek out and kill males, in other words, doing approximately everything a good upper-class Athenian woman would never be permitted to do. She was to be the goddess of the home, skilled in domestic arts and avoiding any kind of public appearance except during ritual events. The Amazons, not so much.

The reality is much more fascinating. All across Central Asia there were and still are groups where girls and boys grow up learning the same arts of horsemanship, weaponry and hunting. They compete against each other in contests, including archery and wrestling. They dress pretty much alike, too, wearing tunics over pants. Many of these communities lived in the region around the Black Sea and eastward into what is now Iran. It was common for girls to form bands and go adventuring, including horse raiding against other groups, so at least the Greeks got that right. They may have also been correct about male babies being given to their fathers, since that is still the practice in parts of Central Asia.

What we didn’t know until fairly recently was that there is historical evidence for these women warriors. The vast areas of “kurgan” burials of horsemen-warriors which are found in a band from Ukraine east to Mongolia were originally interpreted by archaeologists based on the artifacts each contained. It was easy to tell. If a burial contained weapons, the occupant was male; spindles, needles and cooking vessels indicated a woman. DNA analysis is now revealing a different story. Somewhere around a third of the “warrior” burials contain women, and many of their skeletons have exactly the same sort of injuries caused by combat as the men.

Where the Greeks got their stories wrong was assuming the Amazons needed to cut off their right breast in order to use a bow. That would have made sense if they had to use the poorly engineered long, weak Greek bow, but the Amazons, along with the ancient Parthians who so thrashed the Roman armies, used a short, powerful compound bow, much as is still used in Central Asia. There are plenty of YouTube videos showing mounted archers in action, and it’s easy to see how rapidly and effectively these bows can be fired.

Riding a horse, bareback or saddled for any amount of time, requires pants. Different groups have adopted different trouser styles, but it’s all the same. Legs and buttocks have to be covered, and there can’t be fabric wadded up between the rider and the horse. Neither the Greeks nor the Romans, wearers of tunics and togas, were avid horsemen; both waged war on foot and relegated horses to transportation for messengers. On the other hand, the people of the steppes and their neighbors all depended on horses in their daily lives, whether as pastoralists or as warriors, so all wore some sort of garment which permitted them to straddle a horse and ride in comfort for hours at a time.

Constructing pants for a rider is an interesting challenge; a typical plain weave fabric sewed in a conventional pants pattern doesn’t provide the necessary stretch to successfully reach over and around a horse’s barrel. The crotch will tear out every time if the offside leg is swung high and far enough to get across the horse. A twill weave, denim, for example, is somewhat more flexible, but still limiting. Many traditional nomad pants have a crotch gusset or very wide legs, gathered near the ankle to allow space at the top for the straddle. An alternative to the fullness might be to construct pants with narrower legs of some more stretchy fabric, like the modern knits.

Paintings of Amazons don’t show them with baggy pants, but rather with both pants and long-sleeved shirts which fit quite close to the body. On some sculptures there appears to be a hemline, while others don’t show any edges to the garments.

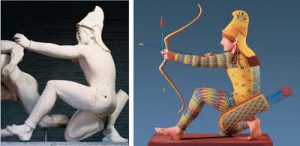

The unpainted vs. the painted Paris

The picture above is of Paris, who is dressed as many of the Amazons are depicted, with long sleeves and pants and a “Parthian” hat which looks like it might be made of felt. His tunic might be woven or even a very lightweight tapestry. His scabbard could definitely be leather, tapestry, or possibly wood with a fabric covering. The question is, what technique made the rest of his clothing? You can see that the pants and sleeves fit quite snugly and the pants are flexing at the knee without a lot of excess fabric. From our modern perspective, we’d probably say “Well, they’re knit, of course”.

Now comes the problem. The first evidence for knitting comes from Coptic Egypt, a number of centuries in the future. Netting? Possibly, but how are the patterns and apparently tight structure achieved? Very light, flexible woven? How would that hold up to the sort of abrasion daily horse riding produces? Was there some other, now-lost fiber technique which created these garments?

It’s all very mysterious. If you can do some research and find the answer, we’d all love to know.