How Silk Helped Us Win World War II

Cathy M Koos

Fabric of any kind, but especially fancy fabric, was scarce in the years during and following World War II. Like Scarlet O’Hara, even curtains were requisitioned for clothing. The silk industry was largely repurposed to manufacturing parachutes, but there was a unique niche making evasion and escape maps for soldiers behind enemy lines.

Maps

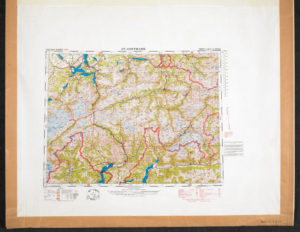

Silk Map of Switzerland, WWII, British Library Public Domain

3.5 million maps printed on silk were used by an estimated 17,000 soldiers to either evade capture or to escape from prison camps. Along with tiny knives, saws, and button compasses, paratroopers had the maps sewn into their boots and uniforms, cleverly concealing from the enemy but easily accessed. Maps were also hidden in Red Cross packages sent to Allied prisoners of war – cunningly pasted inside playing cards and Monopoly boards; and spun into twine and hidden in spools of sewing thread.

First used during World War I, the British intelligence service MI9 resurrected silk maps during World War II and shared the idea with the U.S. Subsequently, both countries began printing silk maps and maps made from a thin but sturdy mulberry leaf tissue. The mulberry leaf tissue was acquired from a waylaid Japanese ship.

As an aside, the Japanese used this technology to make hot air balloons set off into the atmosphere in Japan, with the intent of creating fires on the west coast of America. Coincidentally, one of those balloons landed in my hometown of Volcano, California. Because the balloons were launched to take advantage of winter jet streams, no fires were started.

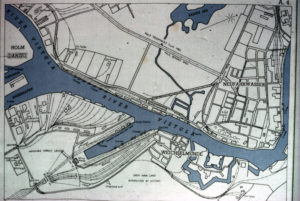

Silk Map, Danzig, WWII, British Library Public Domain

Many of these maps survived and you can find them on eBay and Etsy, sometimes as an intact map and sometimes repurposed into tote bags, dresses, and tiny scraps as pockets on shirts.

Escape and evasion maps are still used today by the military, evolving from silk to rayon in Korea, nylon to plastic during the Vietnam war. The plastic version was short-lived, as it cracked and wore quickly. Today many of these maps are made from Tyvek – just like a Fed Ex envelope.

Dress, Silk Escape Maps, Harrogate, courtesy BBC

Weddings

Even with the war going full swing, couples hopeful of future peace still wanted to marry. Alas, fancy fabrics were scarce and resourceful brides cast their eye on…. parachutes. Soldiers often brought their parachutes home with them, as a memory.

Containing upwards of 20 yards of silk, even if the parachute was damaged, there was plenty of creamy silk ready to be sewn into dresses with all the frills and a long train. Lady Glenconner, once Lady-in-Waiting to Queen Elizabeth II, reminisced about her wartime debut as a 16-year-old wearing a dyed-green parachute debutante dress in her recent memoir In the Shadow of the Royals.

At the height of World War II, my mom joined up as a 17-year-old, entering the US Navy as one of the first WAVES. When she and Dad married, they were both still on wartime active duty and had to wear their Navy uniforms to the ceremony.

Several of my aunts were part of the Rosie Riveter contingent so in 1948 when Aunt Helen set her wedding date, Mom didn’t want Helen to miss out on a wedding dress like she did. Mom volunteered her sewing skills to create a gorgeous wedding gown from Uncle Harold’s war souvenir parachute. Grandma had a treadle sewing machine and Mom set to work cutting up an item that once saved a life and stitched it into a dress to set the stage for a new life together.

Aunt Helen on her wedding day, photo courtesy Pat Koos

Want to read more about the maps? This article relates a fascinating story about the craftiness of one dedicated, mad British inventor:

And if you want to find out how Maidenform Bras and pigeons also helped the Allies win the war, go here after you look closely at the paratrooper’s chest:

https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2013/09/pigeons-in-bras-go-to-war.html