Mutton: The Wooly Dog of the First Nation

Cathy Koos

Chloe is my rescue dog. I have to brush her every day. And every day, I get a big handful of long white guard hair and fuzzy white undercoat and I wonder…is this stuff spinnable?

Figure 1 My Chloe

Chloe’s litter was found in a dumpster in a central valley trailer park, and East of Eden Rescue fostered the pups. I have had Labrador Retrievers for thirty plus years, so when my beloved old fellow went over the Rainbow Bridge at the ripe age of eighteen, I thought about a rescue. Originally, E of E thought the puppies were a Lab cross, but one pup mysteriously had a blue eye, so DNA testing was done on the whole litter. Testing revealed no Lab at all, but mostly Anatolian shepherd and Siberian Husky … and fourteen other breeds. It was an ah-ha moment (or perhaps an oh-no moment) but Chloe had already entered my heart.

True to her Husky ancestry Chloe has a soft double coat, is very talkative, loves to run, and is Husky-size. Also true to her Anatolian ancestry comes her curled tail, her biscuit color, protectiveness, and her aloofness. She is a work in progress for training.

I recently read a Scientific American article on “Mutton, a Salish Woolly dog.” Just as Chloe is evidence of many generations of carefree breeding, Mutton was evidence of five thousand years of a careful breeding program by the Indigenous First Nation Coast Salish women.

Anthropologists and archaeologists have long known that at least 16,500 years ago, early people crossed the land bridge from Siberia to what is now Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. They brought a wide variety of dogs with them, using them to pull carts and sleds, as well as hunting and protection.

Sometime about five thousand years ago, some enterprising, high-ranking Salish women probably noticed a couple of dogs with a double coat – the outer coat comprised of longer guard hairs, but with a wonderful wooly undercoat.

Figure 2 Smithsonian Institute, artist rendering Karen Carr

Other than alpacas, these now extinct dogs are the only indigenous animal in the Americas providing wool for textiles.

Socio-Economic Systems

For the Salish, blankets were currency. The blankets woven by the high-ranking women had immense value, both economical and spiritual. Working together, these blankets could take up to a year to complete. Wrapped around the shoulders of a chief, a newly married couple, a newborn, or a deceased loved one, the blanket was at once spiritual and set aside the recipient as important. During potlatch1 ceremonies, a Salish blanket was a highly valued gift.

Alas, very few intact blanket samples remain, so remaining scraps are carefully guarded and conserved.

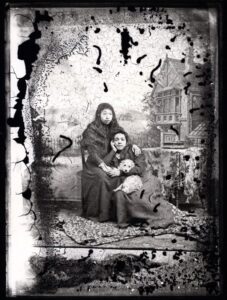

Figure 3 Young women and their Woolly dog, Photo courtesy Chilliwack Museum ca 1800s

According to an interview by KUOW2, Indigenous artist Eliot White-Hall (Kwulasultan) said “the core of Salish cultural philosophy is that through a potlatch, you become wealthy only by giving away.”

The Blankets

Figure 4 Paul Kane, ca 1840s. courtesy Royal Ontario Museum

Woven on traditional upright, warp-weighted loom, the warp was usually traditional plant-based fibers like nettles and Woolly dog fleece, and the weft was a combination of feathers, mountain goat and Woolly dog, liberally dusted with diatomaceous earth3.

Figure 5 Smithsonian Museum, Coast Salish classic-style blanket ca 1838-1842

The blanket was not simply a covering for warmth. The act of weaving itself was sacred, filled with the ancient stories and oral history of a people. The presentation to a fellow tribal member conveyed a sacred spirituality.

Woolworker and historian Sylvia Olsen of Vancouver Island studied some of the remaining samples and found them to range from three to six meters long and very heavy, due to the variety of materials plus the addition of diatomaceous earth for insect resistance.

The Woolly Dogs

In appearance, the Woolly dogs resembled spitz breeds like Samoyeds, Siberian Huskies, and Malamutes, but described by Vancouver as similar in size to a large Pomeranian. Similarities ended with appearance, however, as the Woolly dogs had a unique genetic makeup different from other dogs. DNA studies by the Smithsonian reveal a recessive gene for woolly hair – the same gene in some humans and in the Woolly Mammoth.

This unique breed was developed by the Salish women over a 5000-year period. For genetic isolation, the Woolly dogs were kept separate from the other community dogs to prevent accidental breeding; sometimes kept in their own corral and even on a nearby island. The Woolly dogs were the only dogs treated as beloved pets and allowed in the home. They were fed a rich diet of elk and salmon, to keep their coats in prime condition.

The dogs were regularly brushed and once a year sheared like sheep, using a sharpened mussel shell.

The Woolly dogs were held in such high regard that some were wrapped and buried with their humans. Burial analysis showed that some dogs even had personal agency. According to Chief Janice George, Squamish Nation, “They are alive because they exist in the spirit world. They are the animal. They are part of the hunter; they are part of the weaver; they are part of the wearer.”

Extinction

Unfortunately, shortly after British Navy explorer Captain George Vancouver arrived in the Pacific Northwest in 1752, the Woolly dog quickly became extinct. There are a number of theories on why this occurred. The arrival of Colonial dogs certainly had a direct impact on the breed. Consider, as well, the forced conversion to European belief systems and subsequent dismantling of Indigenous customs and practices. Many ancient practices, especially weaving sacred blankets, were criminalized in an effort to assimilate the people.

Introduction of cheaply made woolen blankets by the Hudson Bay company and the European demand for otter pelts in trade likely promulgated the extinction.

While a few Woolly dogs were glimpsed after 1900, this is likely one of the last dogs between 1935 and 1940 on the East Saanich reserve north of Victoria.

Figure 6 East Saanich Reserve, ca 1935. University of Victoria Library Special Collections

So, Who Was Mutton?

In the 1850s, George Gibbs, a naturalist, explorer, and ethnographer, was gifted Mutton while he was studying the culture and languages as part of Smithsonian Institute’s Northwest Boundary Survey. DNA examination of Mutton’s pelt reveals him to be about 85% Woolly dog. Perhaps his mixed ancestry was why he was gifted to Gibbs.

Figure 7 Mutton’s pelt, Audrey Lin, Smithsonian

By 1859, Mutton had died and his pelt, along with other collected wildlife, was sent off to the Smithsonian where it languished in an archive drawer until rediscovered by Postdoctoral Scholar Audrey Lin in 2021. DNA studies revealed Mutton’s recent ancestors had some interaction with other dogs and was only about 85% Woolly dog. Thus, telling a tale of Colonial dog influence and the beginning of the end for the breed.

There were a couple of sightings of Woolly dogs, and photographed, as late as 1930. Sadly, despite our currently technical ability to clone, it is unlikely that the Woolly dog will be brought back from extinction. Recognition of the Woolly dogs’ contribution to the Salish people has revived a renaissance in Coast Salish weaving from just a few weavers to several thousand artisans.

In the words of Snuneymuxw First Nation (Nanaimo, British Columbia) artist Eliot White-Hill (Kwulasultan) during an interview with KUOW, “It starts to break down people’s understanding of us as a hunter-gatherer society, which is such a simplistic, blanket understanding of Indigenous people in general here in North America. That I think is really where the work of reconciliation can be done. It comes from understanding and empathy and knowing that sense of understanding is a place where empathy can flourish.”

Footnotes

1 Potlatch. An opulent ceremony among North American Indigenous peoples featuring feasting and ceremonial give-away of possessions display wealth or enhance prestige

2KUOW. Seattle National Public Radio station

3Diatomaceous earth. Fossilized remains of diatoms, a type of hard-shelled microalgae; used as an insecticide in some textiles.

References

Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Seattle WA.

KUOW, National Public Radio for Puget Sound, Seattle, WA

Museum of Vancouver, Vancouver, British Columbia.

American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY

Hakai Magazine, Virginia Morell, February 23, 2021, www.hakaimagazine.com

George, Janice Chief. Salish Blankets: Robes of Protection and Transformation, Symbols of Wealth, University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

Smithsonian Magazine, Audrey T Lin and Logan Kistler, December 15, 2023.

University of Victoria Libraries Special Collection.