The Vikings: A Wool Legacy

Cathy Koos

When I think of Viking ships, for some reason I conjure a vision of woven hemp or linen sails, so when I read an article on Vikings and wool sails,by Claire Eamer in Hakai magazine, I was intrigued. And like Alice, I went down the proverbial rabbit hole, chatting with a Danish museum, a school in Norway, author Claire Eamer, and even a friend in the Royal Navy.

Wikipedia Moragsoorm archiwum własne wikingów Jarmeryk

The sheep. Naturally shedding, the Gammelnorsk sau, or Norwegian wild sheep, is believed to be the oldest original short-tailed sheep in Europe. Of modest size, these hardy sheep provided meat, wool, milk and hides to the Viking communities. It has even been said that its “the fleece that launched 1000 ships.” 1 Ideally suited to year-round life outdoors, these hardy little sheep are nimble and self-reliant.

By Thomas Bjørkan – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/

In the early 18th century, sheep imported from England usurped the Gammelnorsk sau or villsau until the ancient breed was nearly extinct. By 1912, however, farsighted plans were afoot to conserve the remaining ancient stock. Now numbering 30,000 head, the breed is considered a Protected Geographical Indication or PGI, reflecting a diligence to preserve this ancient breed.

The Gammelnorsk meat is sweet and tender, slightly gamey. As with many ancient breeds, they are light-footed and have a herd behavior of drawing predators away from the weakest members and towards the strongest members of the herd. Always alert and on guard, both sexes may have horns. The sheep enjoy a mild coastal winter, primarily in Norway, where they graze on heather, herbs, kelp, and seaweed. Double-coated, the villsau naturally shed their fleece in early summer.

And it is that naturally shed wool that made this primitive sheep even more useful to the Norse. These dog-sized sheep with their lanolin-soaked wool is naturally water repellent and has been keeping Norse people warm and fed for millenia. No need for shears, hand plucking is all that is needed. Before knitting became the standard, early garments were produced by nalbinding, a single needle type of knitting.

The environment. Historical records reflect the burning of the heath every year by the local people. Due to the vast number of sheep required to produce not only wool, but meat and hides, indigenous farmers had to keep up with the Vikings’ ever-expanding need for ships and sails. By burning the heath, the farmers encouraged the tender grasses and herbs to grow, while suppressing the heather and pine seedlings. The sheep flourished on the grasses and herbs in the summer, putting on weight and improving their fleece, while the heather provided much needed forage during the hard winter months.

Claire Eamer, www.claireeamer.com

The boats. While two skilled boat makers could produce a modest sized boat in a few weeks from native trees, it may have taken two highly skilled people, mostly women, a year to produce its sail.

The sails. Labor intensive, the wool was spun on drop spindles. Sails were woven on an upright, warp weighted loom. Each boat had its own specification for its square sail. Not too big, not too wide, not too high: a Goldilocks sail. Every community likely had one of those people – we all know them – the tinkerer, the experimenter, who fiddled with the size and shape of the boat and matched its mast, sail, and ballast correctly.

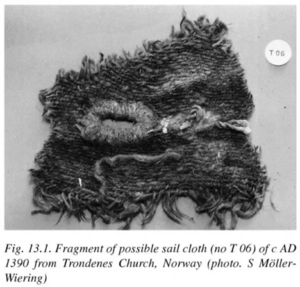

Thanks to King Knut. While shipwrecks have been found well preserved due to cold water, intact sails have not been found with the wrecks due to wool’s propensity to rot. However, we can thank an old Viking law dating back to 1000 CE for this little pearl of King Knut: “The man upon whom responsibility falls shall store the sail in the church. If the church burns, this man is responsible for the sail.” As luck would have it, this obscure law allowed researchers in 1990 to find a scrap of a woolen sail tucked up in the roof of a church in Trondenes dating back to the mid-13th century. Now residing in Viking Ship Museum in Rothskilde, Denmark, this fragment has produced unending useful bits of clues to Viking ships.

Thanks to King Knut. While shipwrecks have been found well preserved due to cold water, intact sails have not been found with the wrecks due to wool’s propensity to rot. However, we can thank an old Viking law dating back to 1000 CE for this little pearl of King Knut: “The man upon whom responsibility falls shall store the sail in the church. If the church burns, this man is responsible for the sail.” As luck would have it, this obscure law allowed researchers in 1990 to find a scrap of a woolen sail tucked up in the roof of a church in Trondenes dating back to the mid-13th century. Now residing in Viking Ship Museum in Rothskilde, Denmark, this fragment has produced unending useful bits of clues to Viking ships.

Sail Manufacturing. Each 85-square meter sail required upwards of 2000 kilograms of wool, an entire years’ harvest of wool from 2000 sheep. In preparation for spinning, the outer guard hairs had to be separated from the inner wool, taking 3-4 people up to 6 months of labor. Hand spinning the wool into 165,000 meters of yarn consumed another 6 months, and weaving on the warp weighted loom consumed another year or two. For one sail. When Knut II was planning his invasion of England against William I, it is thought that he had 1700 ships at his command.

Vikingskibsmuseet, Denmark

By studying the Trondenes fragment, researchers found that both the outer guard hair and the inner wool was used in weaving the sail. The warp was made by the long, strong guard hairs, and the weft was created by the softer inner wool, which fluffed and filled the gaps. After being fulled, the sail was exceedingly strong. As a final treatment, analysis revealed a resinous coating made of fir tar, fish oil, and sheep tallow to give the sail resistance to the wind and some water repellant qualities.

Fast Forward. Now we fast forward to 2016 modern day Trondheim, a fjord community on the central Norwegian coast. Fossen Folk High School is taking out their students on the Braute, a traditionally styled Viking ship. The students have just spent the last school year studying ancient skills necessary to survive and thrive in the Viking age: boat design and building, farming, animal husbandry, and textile production.

The Braute is on her way to the tiny island of Utsetoya where the school’s flock of villsau sheep run wild, kept safe from predators by the surrounding ocean. Recreating an ancient scene, the students are on their way to check on the sheep – the same sheep that kept their ancestors warm and dry. 1Claire Eamer

The wool. As with many ancient sheep breeds, these double-coated sheep blow their coats every spring. Just as in ancient Viking times, the students spread out all over the tiny island, directing the sheep into a temporary pen. In true sheep form, they are sure it is the end of the world. But in less than an hour, all the students are back, and all twenty-two sheep and twenty-eight lambs are in the holding pen. Ewes are temporarily separated from their lambs so hooves can be clipped, and vet checks made.

1Claire Eamer

Then, each ewe is guided over to a tarp and laid on her side. The main event commences with rooing or plucking of the fleece. Each ewe yields about a kilogram of wool, which will be subsequently sorted, washed, carded, spun, dyed, and eventually woven into rugs or sails, or knit into sturdy garments ready to meet the wild Scandinavian climate head on.

And thus, the full circle is completed, with a new generation of students learning the Old Ways, keeping the memory strong.

1Claire Eamer, Hakai Magazine, February 23, 2016, www.claireeamer.com

Resources

The Society for Nautical Research, www.snr.org.uk

Sail, Roskilde Viking Ship Museum, https://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/

The Sheep That Launched 1000 Ships, Nancy Bazilchuk, New Scientist Magazine, 24 July 2004

Old Norwegian Sheep, Wikipedia

Wool Stories, https://www.theecostories.com/post/wool-stories

A Wandering Elf Blog, http://awanderingelf.weebly.com/