The Flow Power of Weaving

“Flow is an optimal state of consciousness, a peak state where we both feel our best and perform our best.” Stephen Kotler

I went to the Kansas City Art Institute, KCAI, for a Fine Arts undergraduate degree. The Fiber Department there is very strong. When I walked into KCAI, I knew I wanted to weave. Some years earlier I had been drooling at a loom that my boyfriend’s mom was weaving on. She was encouraging me to buy my own loom, but I decided to wait until I’d taken a weaving class. I wanted to first experiment to see what I could make, learn about different looms, and then go searching for the perfect one.

During my first semester in the Fiber Department, I was deeply drawn to two very different kinds of fabric: the huge bold woven pieces by Magdalena Abakanowicz and long lengths of exquisitely fine Japanese fabric made for kimonos. The combination of these two led to a series of large-scale weavings that would consume me for over 10 years.

To create most of these pieces, I began by dyeing the yarn, usually cotton or nylon sewing thread, and then wove it on a loom to make installations that were 10 to 30 feet tall. They were light, gauzy, abstract compositions –similar to Color Field paintings. Standing close to one of these large pieces, one might get lost in an atmosphere of glowing color or in the minute details to be found in the intersections of colored threads.

Flame

I would do anything to create such works. The feeling of them burned in my mind. I’ve always slept a bit less than others, but when the visions of these pieces came over me I just couldn’t stop working. For weeks, I would work 12 to 20 hours a day. I really took advantage of what a 24 year old full-time student can do in art school!

The process was very labor intensive: warping 2,000 to 6,000 threads, marking areas to be dyed, and so much de-tangling! I was constantly searching for ways to work more efficiently. With the extra time I saved, I would try larger and more complicated projects. Working on one warp for a year or two was not uncommon.

From the first day I learned how to weave I seemed to feel something in my mind change. I’ve always been interested in a million things, which left my brain swirling in too many directions to really pursue any of them. Weaving demanded a linear procedure that was new to me. You just couldn’t start threading a loom until the warp was made. Planning the steps in very great detail was both my way to do large complicated projects and rather soothing to think about.

Mentally repeating each stage of the process became like a mantra for me. I would think about all the details for the steps I needed to do and envision each one in order to be sure I wasn’t overlooking anything. Just thinking about my art stopped me from worrying about other things. Like a sponge soaking up water, weaving project details absorbed my restless mental energy and turned it into a beautiful piece of art. I was so surprised that by staying focused on the work my hands were doing, I could make an object that made me feel so good during the time of creating it and when I looked at the completed piece.

These art pieces were very healing for me, but there was a hidden secret in all my weavings. To organize so many threads, I created my own number codes and I was constantly doing math to work out details. Arranging thousands of yards of thread was really just one big algebra problem. Yes, I’m outing myself here – I admit it – I like math. Actually, I always did. I never got very far in math because I went to an art school. KCAI didn’t require any more math than the College Algebra class I took at a community college.

Another secret about me, I enjoy reading layman’s science books. Though I kept getting frustrated at how often they mentioned that if you really wanted to get this physics concept you needed to learn the math for it. One day I was reading a neat old chemistry book from 1959, which informed me that to understand acids and bases (used in the chemical reactions of dyeing) I needed to learn the mathematical equations for them. At this point, I lost my temper and decided to re-take College Algebra, which I did in the fall of 2007.

Doing math homework wasn’t easy for me. My crazy artist brain had a hard time choosing the right way to solve an equation. I wasn’t fast and I wasn’t a natural at it, but the discipline I had learned from completing all those big projects helped me know that with determination I could overcome challenges, including completing math problems.

Although I was disappointed at how slow I was, I enjoyed doing it. It may sound odd to say that it made my brain feel good; there was something about this kind of learning that was fun. And, when we got to exponents, I did learn a bit about acids and bases. Each new thing I learned left me hungry to learn more. After College Algebra, I took Trigonometry, Pre-Calculus, and Calculus.

In between the first and second math classes, my artistic interests started to shift. If you leave an artist to ponder mathematical concepts for a few months, don’t be surprised if she starts making art with geometric forms. My house started filling up with different kinds of spherical shapes. Some were constructed with paper and some with woven reed, but all were made with the same obsessive working style as my weavings.

Reed Spheres

This series of experiments led to an Artist in Residence with the Exploratorium, a hands-on museum of science and art in San Francisco. For a traveling exhibit called the Geometry Playground, I made a group of 15 polyhedra (three-dimensional geometric shapes, the cube is the most well known) out of metal.

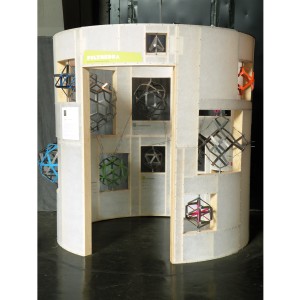

Polyhedra Cylinder

While documenting that set of forms, I became fascinated with how looking at the images of the shapes taught the viewer about geometric concepts. I decided to put them together in a book. After 3 years of research, writing, and Photoshop work, I have completed this project and it is now in the hands of a science writer to edit. Soon, I hope to self-publish my first book, Exploring Polyhedra.

Book Cover

Since then my art keeps shifting in materials and processes. From drawing, painting, basketry techniques, to making polyhedra out of laser cut parts (of paper, acrylic or metal), and simple computer programing to control the glowing colors of LED’s.

This story seems to be about how my interests changed over time, but for me it is a tale of how I learned to work regularly in the ‘flow.’ Also known as ‘getting in the zone,’ it is when you reach a wonderful state of mind where you lose a sense of time and self, but gain a deep focus and are able to accomplish challenging tasks in an effortless way. It is a state known well to creative people and athletes but can be reached doing regular daily tasks, too.

Not long after I wrote this, I heard an interview that covered a good range of this hard to describe experience. Dave Iverson, on KQED’s radio program Forum, spoke to Steven Kotler about his new book, “The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance.” By studying extreme athletes, who needed to stay in the zone to survive their daring feats, he discovered certain steps that anyone can use to reach a flow state.

Exactly how you get in the zone is different for everyone. My path to it came from following my passion for big weaving projects. They scared me a little (but not too much), which elevated me into a kind of focus that would last all night long. For the past few years I have found this special mental state by studying math and science. Lately it has been the challenge of working in different materials, which has brought me to that magical sense of peace blended with a gentle exhilaration.

I hope to get back to weaving soon, but until then I help others to weave. I teach the Evening Weaving Class at the Richmond Art Center throughout the year. In June, I will again teach a two week Computer Jacquard Class at the California College of the Arts. If you would like to access the KQED program: http://www.kqed.org/a/forum/R201403281000