Weaving is simply the interlacing of warp and weft. The principles of weaving are fundamentally the same regardless of the loom. On a standard treadle loom, each warp thread passes through one heddle on one shaft which is raised or lowered. Yet, weavers were always experimenting to see what their looms could do and this led to adaptations of the simple loom. These adaptations probably started out as pick up sticks and segued to cords, rods and other ways to lift pattern bundles, leading to todayʼs use of computerized electronics. The developments followed as the patterns as became more complex and intricate. Over time, new designs were born from the capabilities of the tools and mechanical devises used. New adaptations were put into use as patterns became even more complicated, fostering further adaptation and invention of control devises for the loom.

primitive loom with pattern rods courtesy of American Museum of Natural History

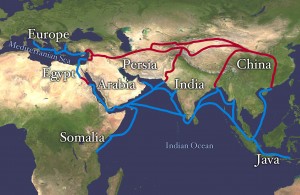

The development of complex weaving patterns was the predominate impetus for the loom’s technical advancement and the importation of intricate textiles from Asia made Europeans look at ways to design and manufacture their own luxurious material. Asia and Europe were connected by the Silk Road, a collection of overland trade routes used by merchants and traders for 3000 years. The routes were important for trade of all kind from China, India, Persia and the Mediterranean and contributed enormously to the development of textiles. This transcontinental route also was the conduit for ideas and various technologies.

Map of the Silk Route courtesy of Wikipedia.com

The central Asian sections of the trade routes were expanded around 114 BCE by the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 AD), which was when the lucrative silk trade began, and ended around 1400, the Middle Ages, when the Silk Road lost its importance as the main trade route when shipping by sea became the preferred way of trade. Silk relics have been excavated along the route indicating advancement in woven patterning over a span of centuries when there was a lucrative silk trade. These include a considerable number of patterned silk pieces dated to the early Tang Dynasty (AD 618-906) or earlier. From these scraps, it is assumed that the Chinese weavers had some sort of drawloom in the 6th or 7th Century. Also, there is a painted scroll from the Song period (960- 1277 ) that pictures a drawloom.

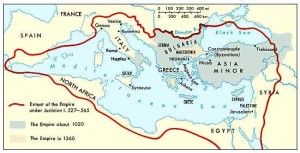

Byzantine Empire courtesy of Christalinks.com

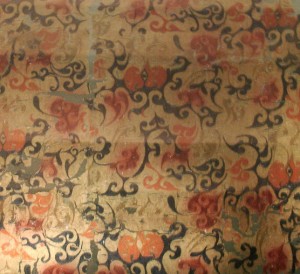

Han dynasty woven silk courtesy of wikipedia

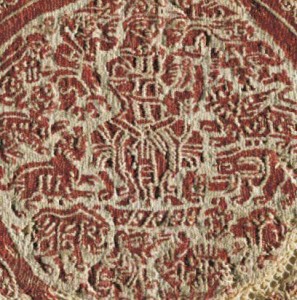

The textiles of the Byzantine Empire reveal the advancement of patterning on the loom, the link between East and West, and the introduction of the drawloom from China. The technique of weaving damask on a drawloom was introduced to Egypt, Spain and the Italian city states. By the 14th century, damasks were seen on drawlooms in Italy. Damasks have historically used one of the 5 basic weaving techniques of the Byzantine and Islamic Weaving Centers of the middle ages and derived their name from the city of Damascus which was a large city active in trading and manufacturing, yet the roots of these structures are from China.

'Orpheus' -patterned textile from Egypt 6th c. A.D. courtesy of Jozan.net

From the 14th century to the 16th century most damask were woven with gold or other metallic threads or additional colors as supplemental brocading wefts. The crossing of paths, routes, ships, information and invention during the transcontinental exchange that occurred on the Silk Routes over a period of 3,000 years is difficult to track.

Detail From Chinese Qing Dynasty Robe 16c-18thc courtesy of Eclectic Museum

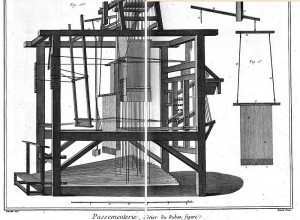

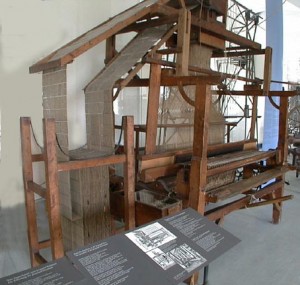

What distinguishes a drawloom from a standard loom is that each warp thread passes through two heddles; a heddle in a set of ground shafts at the front and a heddle in the set of weighted pattern shafts at the back.

Drawloom schematic from WeavingLesson Blogspot.com

Early Drawloom from WeavingLesson Blogspot.com

After the decline of the Eastern Roman Empire (12th-13th centuries), Italian weaving centers were established and played an important role in European silk weaving from the 12 – 13th centuries and into the 18th century.

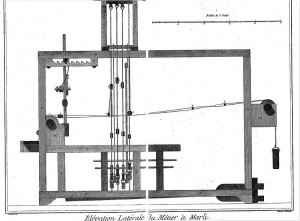

The drawloom was improved in European weaving centers by the use of the comber board. Itʼs not clear when the comber board was first used, but it allowed for a precise

and consistent lifting of the warp minimizing mistakes in patterns and weaving. Jacques de Vaucanson was a French inventor and artist who was responsible for the creation of the first automated loom which was exhibited in the Paris World Exhibition, 1855, illustrating the development of weaving technology in France that was important for the rest of Europe. His proposals for the automation of the weaving process were ignored in his lifetime (1709-1782).

Jacquard loom-note the punch cards on the left side from site of Deutsches Museum

Joseph Marie Jacquard refined Vaucasonʼs developments with an attachment that used punched cards to determine the lift for each shed for the weaver and presented it in Paris in 1804. The Jacquard attachment is a frame with a perforated board fastened horizontally to the base of the machine where the neck-cords of the harnesses pass with attachments needed for lifting the harness.

On the ordinary drawloom, the warp is divided into two sets of threads with a predetermined division determining which warp raises and which lowers, creating a shed for the weavers’ shuttle. To weave a pattern its necessary to raise only those warp threads required to develop the part of the figure. The formation of the pattern depends on the position of each thread.

The Jacquard regulates those movements, eliminating the use of two setts of harnesses found in all drawlooms, and in the place of draw cords there is a perforated board. Jacquard’s devise, initially called the “new French drawloom,” revolutionized the manufacturing of cloth and ultimately shifted the emphasis from pattern development to production output and precision.

jacquard loom in India from site de l'academie de Rouen

The next article tells us how to have some fun! Click on OUTREACH.